Sean Wilson

Posted on Jan 23, 2023 8:23:06 AM

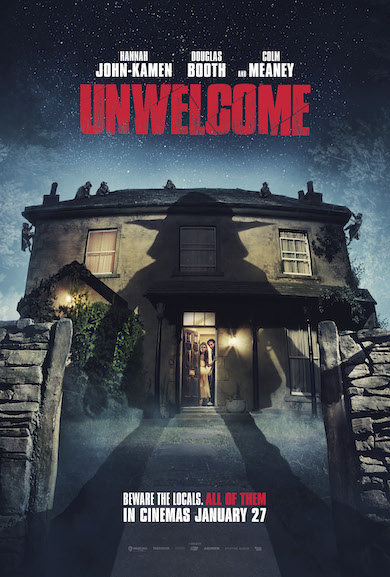

New horror movie Unwelcome throws viewers into a waking nightmare. Hannah John-Kamen (Ant-Man and The Wasp) and Douglas Booth (The Riot Club) play a young couple who are forced to flee London after an appalling attack.

Pitching up at a family cottage in remotest Ireland, the youngsters do their best to acclimate to the eccentric locals. However, there’s another, far more primordial threat lurking in the woods behind the house, one that will ultimately invite a sense of reckoning.

Unwelcome is helmed by director Jon Wright who scored a popular hit with his drunken Irish horror-comedy movie Grabbers in 2012. We were delighted to catch up with Jon to talk his folkloric inspiration for the movie, plus the enduring magic of watching horror at the cinema with a rapt crowd of people.

Was there a particular myth that influenced you in the making of this movie? Or was the story a composite of many different stories?

We delved into Irish folklore and myths and legends. We read a lot of fairy tales and a lot of those I’d read before when I was a kid. I revisited them all.

The thing that struck us was the redcaps. They appear in Irish folklore and in other countries as well. They are goblins who dip their caps in the blood of their victims. That felt like a fun inversion of the leprechaun stereotype. On the surface, we’re talking about leprechaunish-type characters but really these goblins are quite nasty. There’s something about dipping one’s cap in the blood that suggests one is pleased with the outcome.

It was important in this film that the redcaps took pleasure in their work, and they absolutely do.

Yes, when the film gets nasty, it really goes full throttle. But then again, before Disney altered our perception of fairy tales, those stories in their original form were unpleasant. They acted as cautionary tales. You’ve taken it back to that, presumably deliberately?

Absolutely. I really like the unbowdlerised versions of The Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen. The Victorians took out all the nasty bits. But the original tales really play like horror films for children. That’s part of the pleasure. It’s appealing to kids of a certain disposition.

Personally, I’ve always loved things like that. I always wanted to get further forward and watch things that I was too young for or read things that I was too young for. I was quite bloodthirsty in that sense – in fiction, I wanted blood, guts and violence. My sister, by contrast, would get terrible nightmares over anything like that so it depends on the child.

We thought of Unwelcome as a sort of Grimm’s fairy tale for adults. It’s not appropriate for children but there’s a thirst for that in adults of a certain kind. It doesn’t necessarily go away because one is too old for fairy tales. I really enjoy that space and we really leaned into it in terms of the look of the film.

We tried to give it the look and the feel of a fairy tale and to step it away from reality. It doesn’t have kitchen sink grittiness to it. It’s a heightened version of real life, so it is realistic in a sense, but it’s pushed to a point where it almost has the quality of a dream or a nightmare.

This might just be my interpretation but when you look at how the green and red textures have been captured in the film, they look oversaturated and diffused at other moments. Was that intentional?

Yeah, both I and Hamish Doyne-Ditmas, my director of photography, worked hard on the look. We went back to using Panavision Primo lenses, which are these gigantic lenses that they can’t make anymore because they’re full of lead. Health and safety mean they’re prohibited but they have a very particular look. You might recognise the look from umpteen classic movies from the 1980s and 1990s.

We love that soft, diffused look and we really wanted to push it in terms of the colours and go against the trend for desaturated, grey, washed-out grades. One associates those textures ordinarily with realism and a hard edge, the kind of Bourne Identity vibe. We wanted to be the opposite of that and have a dreamlike, hallucinatory, colourful, saturated feeling.

Yes, the use of red, I suppose, is famous throughout history for acting as a warning, right?

We have a brilliant, old-school production designer called John Beard. He cut his teeth working on Terry Gilliam’s Brazil. We went very carefully into the colour palette, and we worked it all through. Because we had the luxury of building a lot of sets, particularly for the interior shots, we were able to carefully control the colours. Different colours mean different things.

“We thought of Unwelcome as a Grimm’s fairy tale for adults.”

Going back to what you were saying earlier, about films that you weren’t supposed to watch and stories that you weren’t supposed to read, are there specific examples that fired your imagination?

I had an experience that I think is quite common among horror directors, at least the ones that I’ve spoken to. I saw a film when I was too young. I went to a birthday party and a friend of mine had a VHS cassette of The Exorcist. I was probably about 12. We all watched it collectively and it scared the crap out of all of us. I thought it was amazing, terrifying but amazing.

So, I asked if I could borrow it and take it home. So I did, and while my parents were out, I watched it again on my own with the lights turned off. I properly terrified myself. I was really, really frightened and I regretted watching it. When I went to bed, I felt that the devil was in the shadows and coming for me somewhere in the house. I had nightmares that lasted for about two weeks. It is a very full-on film.

But then I became fascinated with horror. Rather than scaring me away from ever watching horror films again, it made me think that they were fascinating. Out of that came a life-long love affair with horror movies. I really wanted to see them.

I used to badger my parents to allow me to see them and eventually I was allowed one every Friday night. I’d have mates come over to my house and we’d watch a zombie or a werewolf movie, whatever. Some terrible movies and some great movies in there, too. I’d watch all of them.

They’re all formative at the end of the day, right?

Absolutely. Then I discovered booze and girls, and I discovered that side of life so the Friday nights around my house came to a bit of an end.

I think horror, when it’s good, can be truly great. There are a lot of bad horror films and as a genre, it has a bad name. It’s a notch above pornography, really, in terms of exploitation. You get horrors that are horrible and nasty and don’t have any redeeming qualities. But when they’re good, they’re up there with the Oscar winners because they are inherently dramatic.

You can’t get anything more dramatic than life and death. You don’t have boring passages of talking, wallowing exposition. Horror movies get on the horse and stay on the horse. You get to explore human psychology. I think what’s interesting in films is discovering what makes people tick. We discover what we’re all really thinking and feeling underneath the civilised veneer of how we’re all expected to behave with one another.

That type of thing is really fascinating and in horror, you can get there straight away. You can express it, as long as you have a heart and a sense of compassion. If you have humanity mixed in there with the scares and the thrills and the death-defying terror, then they can be amazing films.

In the cinematic landscape now, people are showing real loyalty toward horror films such as M3GAN. Based on what you’ve said there, it appears to be the communal experience that drives such loyalty.

Different movies match different environments and viewing experiences. But what’s exciting for me about horror, and what I really remember from when I was a kid watching horror movies at the cinema, is you can feel the fear in the room. You can really feel the tension and the excitement. You can also feel the relief and hear the laughter, which is often laughter of relief. It ripples through the cinema.

It’s almost like an animal thing. I don’t know whether it’s pheromones in the air or something, but you can really feel it. There’s something about the collective experience of going to a cinema and everybody being frightened together.

Everyone looks into the abyss together. They’re all looking into what’s scary about life and other people. Everyone faces it together and afterward, we all come out into the daylight laughing about it. That’s a cathartic thing. You don’t get that at home on your sofa. You only get it at the cinema.

Yes, you walk up to the void or the abyss and then back off from it, having survived safe and sound.

Yeah, you do! It’s the coward’s way of facing death. [laughs] We screened the film at the Sitges Film Festival near Barcelona. It’s one of the biggest fantasy and horror film festivals and it was a 1400-seater cinema. It was the first public screening we’d had of the film. I really didn’t know what to expect and it was nerve-wracking. One hopes that the edit is correct and that we got it right and all the work we put into it is about to pay off.

When the first goblin appeared, there was a massive round of applause and it lasted for about 20 seconds. Thereafter there was lots of whooping and cheering and clapping. Again, you don’t get that when you’re watching something on your own. I kind of wish we could get every reviewer to experience the film as I experienced it at Sitges with 1399 other people.

“Horror movies are up there with the Oscar winners because they’re inherently dramatic.”

You mentioned earlier that horror should be rooted in psychology and basic empathy. Unwelcome starts with a very harrowing attack sequence that sets in motion the arc of the characters played by Hannah John-Kamen and Douglas Booth. Is it right to say that the rest of the movie is about their trauma as filtered through the horror of the eventual redcap encounter?

Absolutely. Essentially, those two characters experience a terrible home invasion at the top of the movie. They have PTSD, really. And it’s about them being cured of their PTSD, one way or another. If they’re going to move to the middle of nowhere in the wildest part of Ireland, they need to be motivated to do that.

So, we wanted to set them up at the beginning of the film with the strongest possible motivations. We make sure that the audience believes that they want to get out of town. You want the audience to believe that these characters are going to live in the middle of nowhere. Also, for me, I wanted to set the stall out for the film.

I want to say to people with short attention spans, ‘This is where we’re going to get to. This is the level we can get to, eventually. It’s going to be an intense movie, violent and full-on when it really gets going.’ We say that via the opening sequence and then the film becomes a slow-burn back toward that stage. One is on the rollercoaster going up the clanky slope, approaching the top and it takes a while, even as there’s a nice view en route.

But once it goes over the top, which is the final third of the movie, we ratchet up the tension and the intensity as much as we can.

Linking it back to your 2012 film Grabbers, which I really enjoyed, you sprinkle in occasional moments of levity to offset the mood. Does that also have the effect of amplifying the horror when it eventually arrives?

I just find that in life. I find life quite funny and when people are stressed, in my experience, they tend to make more jokes, not less. That’s a way of coping with things. I like films that allow themselves and the characters to be funny.

The big difference between Grabbers and this is that Grabbers is a horror-comedy. In that film, we were chasing laughs to a certain extent. I don’t think Unwelcome is a horror-comedy although it has comical elements. Personally, it makes me laugh a lot, but then I laughed a lot at Blue Velvet, and a lot of other people didn’t. [laughs] It acts as a relief, doesn’t it?

After a period of intense pressure, if something funny happens or someone says something funny, the laughter that you hear, and I certainly heard this as Sitges, is the laughter of relief. People can let go and stop gripping the seat quite happily.

You’ve rounded up some real Irish scene-stealers who feature in the movie including Colm Meaney, Niamh Cusack and Kristian Nairn. That must be another important facet of the movie?

We were so lucky with the Irish cast because we pretty much landed on our wish list. All the people we want after, we got. Collectively, those guys bring a huge amount of experience to that table but they’re all willing to play the bad guys. They had a lot of fun playing the bad guys.

You hear actors saying this a lot. It’s almost a cliche that actors love playing villains, but I really think that actors enjoy not having to be sympathetic. They don’t have to make the audience like them. In fact, it’s the opposite. The Whelans are the family that you love to hate.

All the actors brought a lot of humour and mischief to it. I like the villains in movies and TV who enjoy their work. I like villains who don’t feel guilty or cut up about it. Such characters take a lot of pleasure in it. There’s something entertainingly hypnotic about that.

It’s also interesting because, with the arrival of the redcaps, I was questioning whether they were, in fact, agents of evil, or are they serving and helping the central couple? It puts the viewer in a moral bind.

The goblins are representative of primal violence, which arguably can be used in the service of good or evil. Really, it’s the people who are evil in this movie, not the monsters.

You’ve hit the nail on the head there. We want the audience to be casting around, particularly in the first half of the film, wondering who the villains are. As in, who am I supposed to be rooting for and who am I up against? We don’t really answer that question until later.

“The actors in this movie had a lot of fun playing the bad guys.”

There’s a Welsh writer named Arthur Machen whose work I really enjoy. He wrote stories about arcane mythology and about the dark, mythological origins of human beings. Ultimately, it’s always been within us, and this past mythology cannot be reconciled with our present-day, binary notion of what constitutes good and evil.

Yes, that’s what’s fascinating when you read these old Irish fairy tales. The morality of the central characters, what they do and how they behave, is quite different from our modern morality. What we assume to be good and evil isn’t what the original writers conceived as being good and evil.

That’s really what the whole premise of the movie is about. It’s about two super-civilised, urban, metropolitan, liberal Londoners who have lost touch with their animal selves, and they’re going to find out what their primal animal desires and fears really are. And they’ll find that out whether they want to or not.

There’s a sense among a lot of people, particularly nowadays, that we spend a lot of our time with our noses in a screen. We are animals, but we’ve lost touch with our animal selves. It’s almost as if we’ve purposefully built a zoo for ourselves that’s separate from nature.

We’re not communing with nature anymore and we’re not in nature anymore. We’re maybe not even a part of nature. I really enjoy those films where people are taken back to nature in one way or another.

You explore that question: are we animals, or are we something different? Taking people into the deep, dark woods is always a fun thing to do. I love shooting in those sorts of places as well, any sort of excuse to shoot in the great outdoors.

On that note, did you shoot in Ireland?

The interiors are a stage near glamorous Watford, purpose-built on an airfield. The exteriors are at various places in both Northern Ireland and Ireland. We shot in a huge forest called Tollymore Forest in County Down. It’s extremely beautiful and I’d recommend anyone visit there if they get the chance.

We also shot in a town called Cong in Ireland where they shot The Quiet Man with John Wayne. There are a lot of statues around the town to commemorate that fact! It’s one of the most picturesque towns in Ireland, almost too picturesque to be believed. It’s got some fantastic pubs and the very best Guinness.

It’s also got these huge logging lorries that travel through the town every 10 minutes or so. It really made me think of Pet Semetary. I like that because it anchored the town in the countryside. It reminded you that the woods were just outside of town and people are taking the woods away.

Maybe also a bit Twin Peaks as well?

[laughs] Always happy to be reminded of David Lynch! When we did the final scene, I thought of Lynch a little bit. This is as out-there as some of my favourite David Lynch moments. The blood-red sky and the unapologetic nature of that final sequence.

Unwelcome is released at Cineworld on January 27.